Our Renta! BLog has already featured two articles that touch on the origins of BL, but how about a history and theory lesson presented by two amazing, fantastic, intelligent scholars? I’m not saying it because these two are my dear cohorts, but because they’re two of the most knowledgeable people I’ve ever met—especially when it comes to their field of expertise, popular culture and manga. So, I arranged a group call with this fabulous pair to discuss the deep, intriguing and sometimes complicated origins of BL, its roots in shojo manga and the feminist and sexual liberation movements, and its misunderstood image.

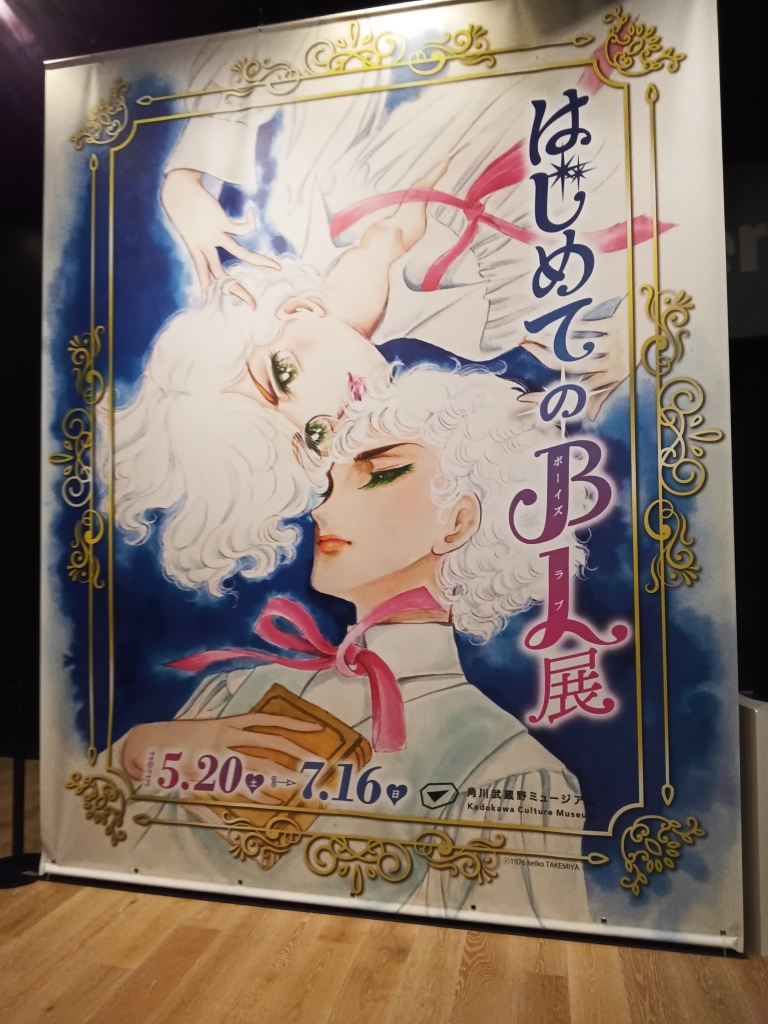

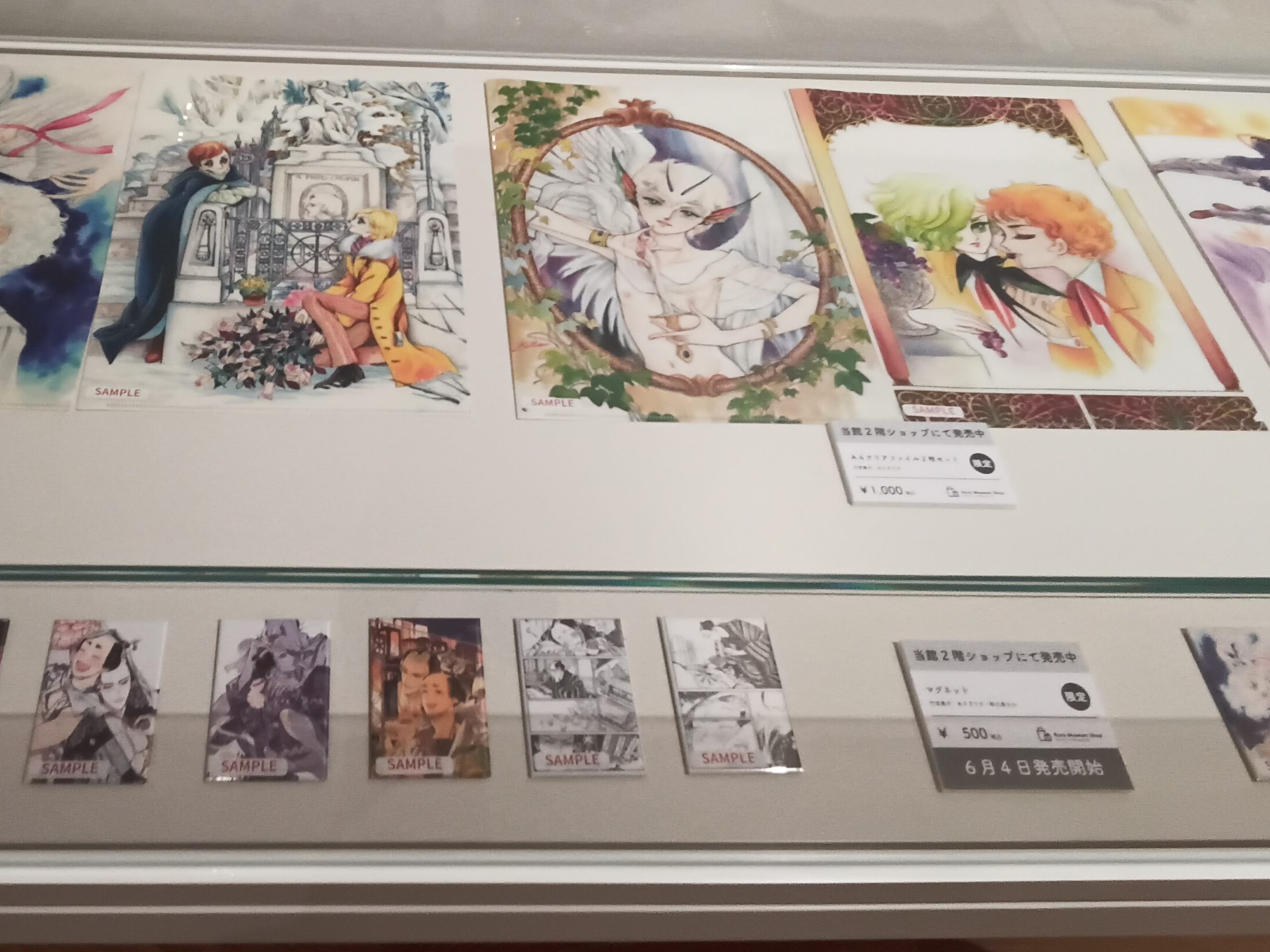

(Disclaimer: portions of the interview were edited after some technical mishaps, but I’ve retained the majority of it as we actually spoke, e.g. occassionally using Japanese surnames first, by habit. Also, I’ll be reusing some pictures from the BL exhibition.)

Alice: First off, how should I introduce you two to our lovely readers?

Maria: I’m Maria, and I’m a Media and Culture professor at Kansai Gaidai University. And, I’m a PhD candidate at the faculty of Manga at Kyoto Seika University.

Lucas: And I’m Lucas, also a PhD candidate at the faculty of Manga at Kyoto Seika University, and I teach Japanese Popular Culture at Kansai Gaidai University.

(It should be noted that Kyoto Seika University is the first university in the world to approach manga as an art and a scholarly subject to be studied, in the same vein as fine art or literature. Though rooted in the student movements of the 60s, much of its pioneering spirit comes from appointing Keiko Takemiya, the legendary mangaka we’ll be heavily discussing, as its president (making her the first female president of a Japanese university). Takemiya-sensei greatly expanded Seika’s approach to manga, and even helped in founding the Kyoto International Manga Museum.)

A: So, I want to hear everything you can tell me about how BL started, but to start off with some basic things I know, Takemiya Keiko featured the first male-to-male kiss in manga in her short story In the Sunroom, in 1970, and opened the way for BL.

M: Kaze to Ki no Uta (The Poem of Wind and Trees, still untranslated in English) came after that.

A: Yeah, Sunroom was kinda like a pilot chapter for it. Actually, when she proposed Sunroom, the editors didn’t wanna publish anything that featured a male protagonist, let alone homoerotic content, so Takemiya, the absolute BAMF that she is, submitted the manuscript at the last minute before publishing, so they wouldn’t have leeway to demand any revisions.

M: So the timeline for the original BL goes, Sunroom in 1970, Moto Hagio’s The Heart of Thomas in 1974 and Takemiya’s Kaze to Ki no Uta in 1976.

L: I think the name changes in the genre are an important part to touch on, if we’re gonna speak about its history. Back in the 70s, when it was shonen ai (boys’ love) the works had a very distinct atmosphere, and they were often referred to as tanbi-kei (“aesthetic style”).

A: I’ve heard that term from reading about Mori Mari, Mori Ougai’s daughter, who wrote gay erotica and she was referred to as a tanbi author.

L: Yes, exactly! Tanbi is all about aesthetics, this dark, cruel, otherworldly atmosphere, usually in European settings, with fragile bishonen and all that. And there’s also Mishima Yukio’s homoerotic descriptions of men, which had the same atmosphere. On that note, let me also show you this book—*pulls out The Codes of Desire: the differences between male and female sexuality, as seen in manga by Prof. Hori Akiko, pictured on the right*—that talks about the origins of BL and its naming conventions. When it started as shonen ai as a part of shojo manga, publishers weren’t like the ones in shonen manga, where they had a clearer system to get their manuscript through the publishers, by seeing what people liked in the reader polls. They had to establish a reputation first, to push something a little more revolutionary through.

A: Or game the system like Takemiya did with Sunroom.

L: More than that. Takemiya Keiko wrote Toward the Terra at the same time as Kaze to Ki no Uta exactly to create that reputation. And, that one doesn’t just show a kiss, like in Sunroom. It starts with a full-fledged sex scene. *he pulls out the first volume of the manga and flips it open, to show the protagonist, Gilbert, in bed with another man* Sure, you can see it’s much more vague and abstract than what we have today, but you can see him coming out of the bed naked and everything. It really doesn’t leave it to the imagination that that’s what’s happening here. Oh, and then he slaps this guy, showing his more tsundere side.

A: Oh, so he’s a bicchi!

L: Yeah, yeah, a proto-bicchi! A lovable slut that learns and grows.

But, see how there’s this very distinct atmosphere here? That’s how it all was until the first Comiket in 1975, when doujinshi started popping up and the words aniparo (anime parody) and yaoi came to be used, which meant that people started drawing BL in other contexts.

A: Because yamanashi, ochinashi, iminashi (“no climax, no punch line, no meaning”) changes that moody vibe completely.

L: Plus, BL started being used only after publishers decided to take this emerging genre and give it structure. So you had the magazine June at first, specializing in shonen ai and more dramatic stories, but then the BL industry expanded into a lot more, which is where you have manga like [Murakami Maki’s] Gravitation popping up.

A: Alright, so, obviously, BL back in the 70s was way different than what it is today. We can see that in things like how the boys were waif-like, in the dark atmosphere, in the focus on tragic love. Oh, and there were hardly any women, or if there were, they were evil villains. Not that shojo in more recent years is all that different when it comes to that, of course. But, when it comes to BL, it was definitely not the same. Where do you think those unique traits of shonen ai came from and how did it develop to be the way it is now?

M: Okay, I can take this one on. So, something we need to get across first is that it all goes back to the Taisho era, when we had the first shojo bunka (girls’ culture) magazines.

A: For our readers, can you define what “shojo” is, in this context? I’ve got an idea, from that lecture we had with Prof. Nakaige Azumi, when she even talked about the man, the legend, Hayao Miyazaki, and his preference for “shojo” heroines, but can you explain it for us?

M: I love that you mentioned Miyazaki; I’ll put a pin on that and get back to it later. Basically, in the Taisho era, a lot of words had to be invented to facilitate Westernization. One, for example, was “art.” That’s not to say there wasn’t art before the Taisho era, but there wasn’t a word to express it. Another such concept was “young girl,” so the word shojo was invented. If you stop to think about it, its kanji, “few” and “woman,” don’t make sense, and that’s exactly because it’s a word invented by necessity, rather than one occurring naturally. The word for “boy,” shonen, means “few years” if broken down by kanji, so you get that it’s a person—a man—of few years. But there was no word to describe the same concept in women, because, up until then, women were defined by only two periods in their lives: daughter and wife. They were daughters and shut in the family home at first, and then, when they came of marriageable age, they became someone’s wife. And mothers, of course. There was no in-between. But with the Taisho era, girls went to school, which meant they left the household and they were no longer just “daughters.” They were out in the world, coming into contact with others, having experiences, and that’s how they became “shojo”—girls.

A; So shojo is basically an adolescent girl.

M: That’s the best way to phrase it, because, think about it: what are adolescents? Rebellious and hormonal. When a woman is a daughter or a wife, the roles are clear-cut and she’s always kept at home, so she can be controlled, but a girl? You can’t control a girl. So now that society has created this new role for women, it also needs to find a way to control, restrict and “protect” them. And how does it do that? Through shojo bunka magazines, which were filled with everything from fashion to moralizing stories. Women themselves also played no role in the creation of content aimed at women back then, or even in Osamu Tezuka’s time. Shojo manga were written by men who wanted to go into shonen manga, but had to pay their dues to the industry first, which meant it was much easier to churn out low-expectations shojo manga. That’s where they developed all those tropes about what a “shojo” needs to be, pure and good—whereas a mature woman, be she a wife, a mother, or whatever, would be depicted as evil most of the time. You know why? Because mature women had sex, and that made them villains. Good girls didn’t have sex before transitioning into wives because sex is for trollops and old women. And if anything, that’s why they were encouraging “homosociality.”

A: Homosociality?

M: Yeah, just two gals being pals and tightly hugging each other, nothing suspicious to see here.

A: So like skinship and athletes slapping each other in the butt?

M: In this case, it’s the idea that if you “date” within your own kind, it’s safe and okay. You could hug another girl tight; that’s okay, because you’re both girls. But hugging a boy? Preposterous. So you’d have artwork of girls lying down in bed together, hugging each other, and it’s supposed to be non-sexual but you can definitely see the subtext there.

But anyway, that was the case back then, before even the 70s. But when the sexual revolution and the feminist movement of the 60s happened, female manga artists decided they’d had enough of all these rules for girls, vague homosociality, and all that, and they didn’t just create female characters with agency, but also male protagonists, because a boy could have even more freedom of movement than a girl. That’s the concept that BL originates from.

A: Wanna go back to the point about Miyazaki?

M: Yeah, just to point out that his gorgeous battlegirl Nausicaä came after Kaze to Ki no Uta. So the discourse about agency in girls definitely predated his free-spirited heroines.

A: Maybe he got some inspiration from the shojo artists of the time, then?

M: Actually, one of the people we should praise about the development of the battlegirl and all this talk about agency is Maki Miyako, awesome shojo artist and the wife of Matsumoto Leiji. She was his advisor on how to write female characters, which is why we have badass female characters like Queen Emeraldas.

A: But what’s interesting there is that, while many creators were starting to give girls agency, Takemiya and others decided to focus on stories with male protagonists, aimed at girls. Was it because there was an even wider range of stories to tell that way?

M: And many more things to express. Think for example of Fire! by Mizuno Hideko, which predated even Takemiya’s work. For the first time, girls were given a male protagonist in a shojo manga, not to identify with him, but to find him hot and, maybe, imagine stories about him with his bandmates.

L: Which ties in with the emergence of Comiket, doujinshi and yaoi. If you think about it, the BL culture we have today is owed primarily to those women that would do unpaid labor to make their own doujinshi off such manga, just for the fun of it and love for the story. *He brings out the book Aniparo and Yaoi by Nishimura Mari.* You can see it here, that the numbers of participants and attendees were rising year by year, but it’s with shonen manga like Captain Tsubasa and Saint Seiya that the numbers skyrocket, because of the love for making stories about these male characters. And, the women participating in this culture were super serious about this, it wasn’t just any simple hobby. *He brings out another book* You know what this is? It’s a catalogue of all the artists producing yaoi for any specific fandom, Saint Seiya in this case, and you can even find the artists’ actual addresses here to come in contact with them. And, see how it very specifically says “for girls” on the cover?

A: I guess this talk about female creators, female agency, etc. might be a good point to bring up the dreaded topic of yaoi ronsou and all the controversies surrounding BL. Obviously BL has evolved to the point that a lot of gay men openly list it in the gay media they consume, but that hasn’t always been the case and a lot of people still have reservations about it.

L: I’ll just start by pointing out the recent ban of BL at a Hong Kong publisher, or the arrest of a BL circle in a Chinese event a few years ago. BL fans over there have had to create what they like under other names, like “bromance” manga. And, we’ve seen how BL fans have had to create and enjoy these works using all manners of rigid rules that are very “gatekeepy” but, all in all, serve as protection, like it happens in the namamono community.

A: Which is to say?

L: All of those arguments of problems that people have with BL come from an idea of false “universality” of those works (as in, they’re available for everyone to read, therefore they must appeal to everyone’s tastes/ethics/beliefs) or from a supposition that BL and the girls reading it are already “culturally accepted” and thus, the people making and consuming BL are doing so from a position of social privilege. In this context, the protective gatekeeping seen in Japanese otaku circles shows that BL fans understand that they’re “the weakest link” of many cultural/social discussions (alongside other otaku) when it comes to issues of regulating desire and might face consequences, even imprisonment. The gatekeeping is a survival strategy.

M: Also, a lot of people who clutch their pearls at BL don’t realize that, from its origins to now, it was never made to be a realistic depiction of LGBT people but an escapist fantasy for socially repressed women.

L: Exactly. And people don’t realize the long history behind it and the reasons for it being the way it is. Another thing they don’t realize is that labels like shojo, shonen, josei muke (for women—commonly BL), dansei muke (for men—commonly porn), all of those titles are just industry marketing terms—not restrictions saying “this isn’t for you.” The bishojo figures I like are typically sold at the dansei muke section, so does that mean a gay man like me isn’t allowed to buy them? Of course not, because at the end of the day, we can all enjoy what we like.

A: This might be a good point to wrap up. Thank you both for the interview! Anything else you wanna leave for our readers?

M: Yeah, to remember that BL has a long history, going back to women’s rights and sexual liberation, and it goes way deeper than the surface level people usually see.

L: And, to always keep in mind that the BL we enjoy today was built on the unsung, unpaid labor of all the doujinshi creators that gave it their all back then out of love for the game.

One thought on “Interview: three otaku discuss the origins of BL and sing Keiko Takemiya’s praises”